Few things seem to stir as much controversy among neighboring waterfront property owners as piers. Common complaints range from concerns about the impact of a proposed pier on a neighboring owner’s viewshed, impairments to navigation, and encroachment into another owner’s riparian area. When dealing with such disputes, it’s wise to get out in front of as many issues as possible before construction begins. Otherwise, there’s a risk that the dispute will devolve into messy and expensive litigation, as a recent ruling from the Virginia Supreme Court in a dispute that has thus far spanned nine years illustrates.

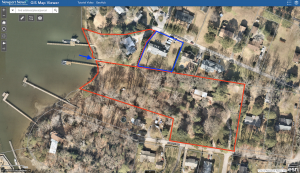

The case involves a pier built by a non-waterfront property owner named Garner. Garner’s property enjoyed an appurtenant easement across the property of the nearby waterfront owner, Edwards. That easement permitted Garner to build a pier near the property line between Edwards and an adjacent waterfront owner, Joseph. The layout is illustrated below, with Garner’s property outlined in blue and Edwards’s and Joseph’s properties outlined in red:

Garner applied for a permit from the Virginia Marine Resources Commission for a pier in 2012. When agency staff notified Edwards and Joseph about the proposal, both filed protests. Edwards complained that the easement did not give Garner the right to build a pier but instead only to cross her land. Because the agency does not have jurisdiction to make binding rulings on property rights, the agency declined to issue a permit until Garner had established his right to do so through the judicial system.

Garner filed suit against Edwards in 2015. That suit resulted in a judgment declaring that Garner had the right to build a noncommercial pier “confined to an extension in a straight line of the Easement into Deep Creek to the low water mark and beyond.”

Garner then again sought a permit from the VMRC. When his case first came up for hearing, counsel for Edwards informed the agency that Edwards intended to appeal the decision. Because of that, the agency continued the hearing. When the Supreme Court did not agree to hear the appeal, the agency rescheduled the hearing. Edwards and Joseph again protested the pier, the latter arguing that the pier ultimately encroached on Joseph’s riparian area. The agency noted that it did not have jurisdiction to determine riparian area encroachments and issued the permit. Garner then proceeded to build a substantial pier, as shown in the aerial photo below:

Joseph then got creative. In 2018, he filed suit against Edwards in the circuit court seeking a riparian apportionment. Joseph did not join Garner as a defendant or otherwise notify him of the pendency of the suit. Joseph and Edwards then reached an agreement as to the riparian area for each of the properties, which was embodied in a court order. Unfortunately for Garner, Joseph’s riparian area delineated in that order included a portion of Garner’s pier.

Joseph then sent a notice to Garner demanding that Garner cease trespassing and using what he termed Garner’s “illegal pier.” Garner then sued, seeking to set aside the apportionment order. Garner argued that Joseph and Edwards knew that Garner had a material interest in the apportionment proceeding yet failed to notify him or join him as a necessary party. Joseph and Edwards responded, arguing that Garner did not have standing to challenge the riparian lines and was not a necessary party because Garner did not own a fee simple interest in waterfront property in the area. The trial court agreed with Edwards and Joseph and dismissed the case.

The Virginia Supreme Court reversed that decision, ruling recently that Garner was a necessary party to the apportionment suit. The court noted that anyone who has a material interest in the subject matter of a suit that is likely to be diminished or defeated is a necessary party. The court further noted that, because the easement granted Garner the right to build a pier, it conveyed “the necessary riparian right to fulfill that purpose.” That riparian right to build a pier was a material interest that was likely to be diminished or defeated in the apportionment suit, so Garner was a necessary party. Because Garner was not joined, the apportionment order was subject to being set aside as void. The court remanded the case for further proceedings.

Despite winning at the Virginia Supreme Court, Garner is still in a precarious position. It is still possible for Joseph or Edwards to file an apportionment action with Garner included as a party, and that suit could result in a finding that Garner built his pier into Joseph’s riparian area and must remove the encroachment. While Garner likely thought that his suit against Edwards was the end of the matter, he would have been well-advised to have brought an apportionment suit when Joseph brought up the possibility of an encroachment during the hearing before the VMRC and before starting construction. Failure then would have merely resulted in a redesign of the planned pier and a modification of the permit. Failure now will require at least a partial demolition of the existing pier and could require a total demolition and reconstruction elsewhere.

The Virginia Supreme Court’s ruling in the matter is available here. If you are interested in waterfront property law issues, be sure to check out the firm’s Waterfront Law Blog.

Matt Hull is a Pender & Coward attorney focusing his practice on eminent domain/right of way, local government, and waterfront law matters.Disclaimer

The materials on this web site have been prepared by Pender & Coward, P.C., for informational purposes only and are not legal advice. This information is not intended to create, and receipt of it does not constitute, a lawyer-client relationship. Internet subscribers and online readers should not act upon this information without seeking professional counsel. Do not send us information until you speak with one of our lawyers and get authorization to send that information to us. Information sent without prior authorization may not be protected as a privileged and confidential attorney-client communication.

Leave A Comment