We just came back from a meeting of the International Governing Council of the International Right of Way Association in New Orleans, so it seems appropriate to post about a recent case out of New Orleans, involving everyone’s favorite delicious New Orleans bite to eat, oysters. The United States Court of Federal Claims recently handed down its opinion dismissing Campo v. United States. The plaintiffs sued the United States for inverse condemnation of their oysters and oyster beds because of the opening of the Bonnet Carré spillway. (Oysters require a certain salinity to survive; the spillway dumps out fresh water; too much fresh water for too long and the oysters can die). The case had gained some notoriety previously when the plaintiffs survived a motion to dismiss the court’s lengthy opinion, Campo v. United States, 157 Fed. Cl. 584 (2021), — which was written up in various places including here and here –being notable in part for including a John Locke quote.

We just came back from a meeting of the International Governing Council of the International Right of Way Association in New Orleans, so it seems appropriate to post about a recent case out of New Orleans, involving everyone’s favorite delicious New Orleans bite to eat, oysters. The United States Court of Federal Claims recently handed down its opinion dismissing Campo v. United States. The plaintiffs sued the United States for inverse condemnation of their oysters and oyster beds because of the opening of the Bonnet Carré spillway. (Oysters require a certain salinity to survive; the spillway dumps out fresh water; too much fresh water for too long and the oysters can die). The case had gained some notoriety previously when the plaintiffs survived a motion to dismiss the court’s lengthy opinion, Campo v. United States, 157 Fed. Cl. 584 (2021), — which was written up in various places including here and here –being notable in part for including a John Locke quote.

This time the claim did not survive, as the court determined that the plaintiffs’ oyster leases did not give them the right to sue the government for alleged damage, although we did get another John Locke quote in the opinion. The Court of Federal Claims framed the question as “whether Louisiana state law prevents plaintiffs from maintaining the instant Fifth Amendment takings claim against the government.” Our John Locke quote for this outing:

[T]he society or legislative [body] constituted by them . . . is obliged to secure every one’s property . . . . And so, whoever has the legislative or supreme power of any commonwealth, is bound to govern by established standing laws, promulgated and known to the people . . . [which are to be enforced by] indifferent and upright judges who are to decide controversies by those laws . . . .

The government argued that plaintiffs’ claims are not permitted under applicable state law, and the court agreed.

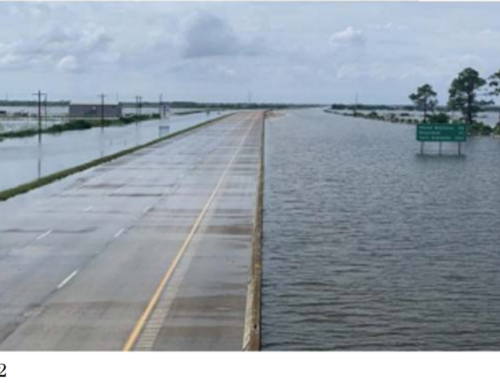

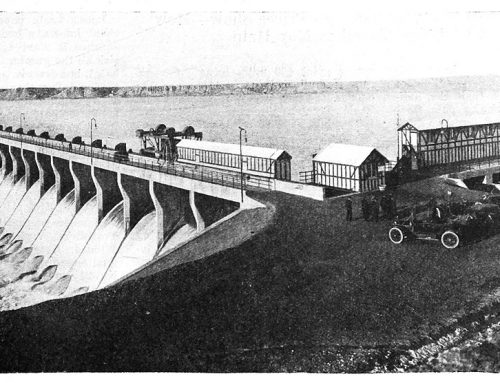

The court first reviewed the history of the Bonnet Carre Spillway, and the specific Louisiana statutes involved. In response to the Great Mississippi flood of 1927, the United States Army Corps authorized the construction of the Bonnet Carré Spillway in 1928. The spillway was completed in 1931 as a flood control structure in St. Charles Parish, Louisiana about 32.8 miles west of New Orleans. The spillway allows floodwaters from the Mississippi River to flow into Lake Pontchartrain and thence into the Lake Pontchartrain Basin. The spillway is opened when existing conditions, combined with predicted river stages and discharges, indicate that the mainline levees in New Orleans and other downstream communities will be subjected to unacceptable stress from highwater. In 2019, the Corps opened the Bonnet Carré Spillway for a total of 123 days, first from 27 February until 11 April and then from 10 May until 27 July. These two openings released nearly ten trillion gallons of freshwater from the Mississippi River into oyster estuaries lowering the natural and essential salinity levels of the waters and marshes where plaintiffs’ oyster leases are located. On 13 June 2019, the Governor of Louisiana, “John Bell Edwards, sent a letter to the United States Secretary of Commerce” admitting “[t]he extreme influx of freshwater [from the Bonnet Carré Spillway opening] has greatly reduced salinity levels in our coastal waters and disrupted estuarine productivity.” (quoting the Governor’s Letter). The Governor further stated: “The most recent sampling of oyster reefs indicated a mortality range of 14% up to 100%. Private oyster leaseholders in nearby areas have indicated to [the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries] they have suffered between 50% and 100% mortality on their oyster reefs, with additional mortalities still ongoing in multiple areas.” (quoting the Governor’s Letter).

The plaintiffs filed a complaint alleging:

As a direct, natural or probable consequence of the opening of the Bonnet Carré Spillway during the year 2019, plaintiffs and the putative Class members have been deprived of the use, occupancy and enjoyment of their personal (oyster stock) and real (oyster beds and reefs) property, resulting in a permanent taking of their property for a public use, without payment of just compensation.

The court issued a 39-page opinion in December of 2021 denying the government’s Motion to Dismiss in Part. See Campo v. United States, 157 Fed. Cl. 584 (2021). The court noted in that opinion that “the government concedes when plaintiffs sell oysters they are ‘paid for the fruits of [their] effort,’ and plaintiffs demonstrate rights to exclude, destroy, use, possess, sue third parties for damages, recover for larceny, alienate, and enjoy the fruits of selling oysters.” The court therefore previously concluded, “[u]nder Louisiana precedent, federal common law, and Lockean labor theory, plaintiffs have shown compensable property rights in oysters” as “against third parties, such as the government in certain circumstances.”

However, the government again moved to dismiss plaintiffs’ complaint arguing this time that “[p]laintiffs’ claim fails because oyster leases in Louisiana are subordinate to actions taken in furtherance of integrated coastal protection, including actions taken for the purpose of . . . flood control, like the 2019 operation of the Bonnet Carré Spillway.” Louisiana has enacted an extensive statutory scheme, which heavily regulates oyster leasing activities on state-owned bottoms. The court conclude this time that the Louisiana statutory scheme does not grant any right to maintain any action against the state, any political subdivision of the state, the United States, or any agency, agent, contractor, or employee thereof for any claim arising from any project, plan, act, or activity in relation to integrated coastal protection. Much of the opinion is dedicated to various arguments about statutory construction where the plaintiffs attempt to argue that the spillway at issue is not “integrated coastal protection.” The court concluded that under Louisiana law that the spillway is part of “integrated coastal protection.” This is enough to to have the case dismissed given the applicable Louisiana statutes.

Of interest to property rights nerds, the opinion goes on to analyze various (unsuccessful) attacks by the plaintiffs on the constitutionality of Louisiana’s statutory oyster lease regime, including the unconstitutional conditions doctrine, Tyler v. Hennepin County, and Knick v. Township of Scott:

VII. The Constitutionality of Louisiana’s Oyster Regime

Plaintiffs further oppose the government’s Motion by asserting state law cannot constitutionally prevent plaintiffs from maintaining Fifth Amendment takings claims. See Pls.’ MTD/MSJ Resp. at 9-10 (“It is true that state law defines the scope of [p]laintiffs property interests . . . [but] this statute attempts to prevent Plaintiffs from pursuing their federal claims for the taking of their property . . . [this] conflicts with the Constitution and federal takings law.” (emphasis omitted)). In support of their constitutional argument, plaintiffs [*56] cite myriad cases and doctrines. First, plaintiffs contend “the Supremacy Clause of the [United States] Constitution” prohibits sections 56:423(A)(1) and (B)(1)(a) from “preventing lessees from raising certain [takings] claims against the [government].” Id. (emphasis omitted) (quoting Def.’s MTD/MSJ at 11). In a closely related argument, plaintiffs allege the unconstitutional conditions doctrine, which according to plaintiffs “holds that even if a state has absolute discretion to grant or deny any individual a privilege or benefit, it cannot grant the privilege subject to conditions that . . . induce the waiver of that person’s constitutional rights,” bars Louisiana from indirectly “limiting [p]laintiffs’ exercise of their constitutional right[ to bring a takings claim] . . . by offering [p]laintiffs oyster leases subject to the condition that they waive their constitutional rights to compensation for the taking of their property.” Pls.’ Suppl. Br. at 1-4 (citing Koontz v. St. Johns River Water Mgmt. Dist., 570 U.S. 595, 608, 133 S. Ct. 2586, 186 L. Ed. 2d 697 (2013)). Plaintiffs next argue restricting their ability to sue renders the Takings Clause “a dead letter” and violates the Supreme Court’s pronouncement “a [s]tate, by ipse dixit, may not transform private property into public property without compensation.” Id. at 9 (first quoting Hall v. Meisner, 51 F.4th 185, 189-90 (6th Cir 2022); and then quoting Webb’s Fabulous Pharmacies, Inc. v. Beckwith, 449 U.S. 155, 164, 101 S. Ct. 446, 66 L. Ed. 2d 358 (1980)). Specifically, plaintiffs [*57] argue “Louisiana . . . banning the ability of these property owners to exercise their constitutional rights under the Fifth Amendment is an improper attempt to sidestep the Takings Clause” to the benefit of the State of Louisiana. Id. at 10. Finally, plaintiffs conclude Louisiana’s regulatory scheme “places an unjustifiable burden on [t]akings plaintiffs” in violation of Knick v. Township of Scott, in which the Supreme Court stated “[t]he Fifth Amendment right to [bring a federal lawsuit for] full compensation arises at the time of the taking.” Id. at 13-14; Knick v. Township of Scott, 139 S. Ct 2162, 2170, 204 L. Ed. 2d 558 (2019). Plaintiffs therefore request the Court strike down sections 56:423(A)(1) and (B)(1)(a) as unconstitutional. See Tr. at 91:24-92:1 (“[PLAINTIFFS:] The federal government is following state law . . . but no court can enforce an unconstitutional law.”); Tr. at 110:23-25 (“THE COURT: So, again, is [your request] that [56:423(A)(1)] should be completely stricken? [PLAINTIFFS:] I believe so . . . .”).

The government’s primary objection to plaintiffs’ constitutional arguments is plaintiffs’ constitutional “claim[s] . . . would have to be brought against the state.” Tr. 129:24-25. The government argues it is the incorrect party to defend Louisiana’s statutory scheme because it is “just following state law,” not creating or enforcing it. [*58] Tr. at 91:22-23. Specifically, at oral argument, the government stated, plaintiffs’ “claim is against the state [of Louisiana]. If plaintiffs really think that they had some pre-existing right to sue the United States and that was taken from them, that claim is only viable against the State of Louisiana in a court that has jurisdiction . . . .” Tr. at 93:17-21. The government therefore believes plaintiffs “should have sued [Louisiana] at the moment that they were contemplating entering into [these] lease[s]” because “[t]hat’s the point when they lost their property right [to sue] . . . if they had such a property right to begin with.” Tr. at 138:8-14. Addressing each of plaintiffs’ arguments, however, the government argues “[p]laintiffs’ position . . . assumes every property right includes some sort of pre-existing right to pursue a Fifth Amendment claim . . . [even though] ‘[i]t is well settled that “existing rules and understandings” and “background principles” derived from . . . state, federal, or common law, define the dimensions of the requisite property rights for purposes of establishing a cognizable taking.'” Def.’s MTD/MSJ Reply at 3 (quoting Acceptance Ins. Cos. v. United States, 583 F.3d 849, 857 (Fed. Cir. 2009)). The government argues the parties agree Louisiana [*59] “state law defines the scope of [p]laintiffs’ property interest[s,]” and Louisiana law, according to the government, “defines [p]laintiffs’ property right[s] as” without “the right to sue the United States for actions taken for ‘integrated coastal protection.'” Def.’s MTD/MSJ Reply at 3-4 (citing La. Rev. Stat. § 56:423(A)(1) (2016)); Def.’s Suppl. Br. at 18; see also Pls.’ MTD/MSJ Resp. at 5 (noting “independent source[s] such as state law” define the scope of property rights (quoting Murr v. Wisconsin, 582 U.S. 383, 137 S. Ct. 1933, 1951, 198 L. Ed. 2d 497 (2017) (Roberts, C.J., dissenting))). The government distinguishes the instant case from the unconstitutional conditions doctrine cases cited by plaintiffs on the grounds plaintiffs “were never granted” the right to sue in the first place. Tr. at 138:22. The government therefore argues there was no conditioning of a benefit on the forfeiture of a right because the right never existed. See id. The government likewise distinguishes those cases in which states were prevented from turning, “by ipse dixit[,] . . . private property into public property without compensation” on factual grounds, arguing no such transformation occurred here because plaintiffs never had a property interest in the right to sue for a taking. Webb’s Fabulous Pharmacies, Inc., 449 U.S. at 164; see Tr. at 120:3-14. [*60] Finally, the government contends Knick is inapposite here, where “the state owns the water bottoms [so] . . . can define the property interest the way [it] want[s].” Tr. at 126:2-4.

The Court next turns briefly to each of plaintiffs’ constitutional arguments. At the outset, however, the Court notes “[p]ursuant to express grants by Congress, the jurisdiction of the Court of Federal Claims is primarily over monetary claims against the federal government.” Giesecke & Devrient GmbH v. United States, 150 Fed. Cl. 330, 342 (2020). This court is largely without power to grant declaratory relief. See United States v. Sherwood, 312 U.S. 584, 588, 61 S. Ct. 767, 85 L. Ed. 1058 (1941) (“[I]t has been uniformly held . . . that [the Court of Federal Claims’] jurisdiction is confined to the rendition of money judgments in suits brought for that relief against the United States.”); 28 U.S.C. § 1491(a)(1) (defining the jurisdiction of the United States Court of Federal Claims as, primarily, “jurisdiction to render judgment upon any claim against the United States”). Indeed, the Supreme Court has expressly stated, “the Court of [Federal] Claims has no power to grant equitable relief.” Bowen v. Massachusetts, 487 U.S. 879, 108 S. Ct. 2722, 101 L. Ed. 2d 749 (1988) (quoting Richardson v. Morris, 409 U.S. 464, 93 S. Ct. 629, 34 L. Ed. 2d 647 (1973) (per curiam)). Further, in contrast to the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, the RCFC do not permit a “[state] attorney general [to] intervene” in this court when a state law is challenged [*61] on constitutional grounds. Compare Fed. R. Civ. P. 5.1, with RCFC 5.1. This court, in which Louisiana cannot defend its laws and the Court is without jurisdiction to declare a state law unconstitutional, is therefore, unlike the Louisiana Supreme Court, not the most appropriate forum for considering plaintiffs’ request to “completely stri[ke]” down Louisiana’s statutory scheme. See Tr. 110:23-25; see also Tr. at 91:22-23; Def.’s Suppl. Br. at 8 (“If plaintiffs intend to challenge the constitutionality of a statute, they must do so in a forum with jurisdiction to hear such a claim . . . .”); Pls.’ Suppl. Br. at 7 (“[T]o the extent that the Court sees a need to declare the state law unconstitutional, it may be appropriate to notify the State of Louisiana.”). The Court, in addressing plaintiffs’ constitutional arguments, therefore cautions its analysis is not necessary to holding plaintiffs’ claim must be dismissed, which relies not only on Louisiana’s statutory scheme, but on plaintiffs voluntarily assenting to lease contracts imposing the relevant restrictions on their rights in the oysters.

Whether Louisiana Law Violates the Unconstitutional Conditions Doctrine

Plaintiffs contend “Louisiana . . . is prohibited [*62] by the [United States] Constitution from . . . indirectly” limiting plaintiffs’ “exercise of their constitutional rights” by conditioning oyster leases on the waiver of their “right[] to compensation for the taking of their property.” Pls.’ Suppl. Br. at 3-4. Plaintiffs argue the unconstitutional conditions doctrine makes clear “[t]he power of the state . . . is not unlimited[;] and one of the limitations is that [states] may not impose conditions which require [the] relinquishment of constitutional rights.” Id. at 2 (quoting Frost v. R.R. Comm’n, 271 U.S. 583, 594, 46 S. Ct. 605, 70 L. Ed. 1101 (1926)). Plaintiffs, citing Koontz v. St. Johns River Water Management District, emphasize the Supreme Court’s pronouncement, “[t]he government may not [condition] a benefit . . . on a basis that infringes . . . constitutionally protected . . . freedom[s].” 570 U.S. at 608 (quoting United States v. Am. Libr. Ass’n, 539 U.S. 194, 210, 123 S. Ct. 2297, 156 L. Ed. 2d 221 (2003)). Thus, plaintiffs conclude it is unconstitutional for Louisiana to “offer[] plaintiffs oyster leases subject to the condition that they waive their constitutional rights to compensation for the taking of their property by the [government].” Pl.s’ Suppl. Br. at 3-4.

In response, the government first argues the unconstitutional conditions doctrine is “not a viable argument against the . . . government” because Louisiana, not the government, “took the action which [allegedly] took” plaintiffs right to maintain a takings claim. Tr. 135:13-17. Addressing the doctrine itself, the government primarily argues it is inapplicable because plaintiffs do not have a “preexisting compensable property right” in the ability to sue, meaning Louisiana could not have “coerce[d] plaintiff[s] into giving up that right.” Def.’s Suppl. Br. at 1-2; Tr. at 22:1-6 (“[THE GOVERNMENT:] [T]hey do not have that right [to sue for a taking], but I would not say it’s a forfeiture, because that suggests that they had that right to begin with.”).

The unconstitutional conditions doctrine applies when a “condition is . . . imposed” requiring a person “surrender . . . [a] constitutional right as a condition of [a government’s] favor” such that something “has been taken.” Koontz, 570 U.S. at 608; Frost 271 U.S. at 594. “Where . . . [a] condition is never imposed, nothing has been taken[,]” so the “remedy—just compensation—[mandated by the Fifth Amendment] for takings” is inapplicable. Koontz, 570 U.S. at 608-9 (emphasis omitted). In Frost, for example, which plaintiffs refer to as “the seminal unconstitutional conditions case[,]” Pls.’ Suppl. Br. at 1-2, California required the plaintiff, a contract carrier, to submit to regulation as a common carrier and obtain a certificate of public convenience before continuing to operate its business on public highways, Frost, 271 U.S. at 590. The plaintiff, who operated its business on public highways freely until the enactment of the law at issue, was suddenly “compel[led] to surrender . . . [a] constitutional right as a condition of [the state’s] favor.” Id. at 594. The Supreme Court therefore struck down California’s statute as applied. Id. at 599. Likewise, in Koontz, the plaintiff challenged a local government’s “demand for [real] property [in exchange for approving] a land-use permit” application. 570 U.S. at 619. The Supreme Court, rather than addressing the merits of the case, held such a requirement must satisfy its unconstitutional conditions doctrine precedent in the land permitting context. Id. (citing Nollan v. California Coastal Comm’n, 483, U.S. 825, 107 S. Ct. 3141, 97 L. Ed. 2d 677 (1987); Dolan v. City of Tigard, 512 U.S. 374, 114 S. Ct. 2309, 129 L. Ed. 2d 304 (1994)). In both Frost and Koontz, the government imposed “excessive conditions” on preexisting rights. Koontz, 570 U.S. at 609. In Frost, the plaintiff’s preexisting right to operate privately on public highways was conditioned on the plaintiff submitting to the “regulative control of the” California Railroad Commission and obtaining “a certificate of public convenience and necessity.” Frost, 271 U.S. at 590. In Koontz, the plaintiff’s right to use and “develop . . . [the] northern section of his property” was conditioned on him making “one of two concessions” involving granting the local government a “conservation easement on” much of his “remaining 13.9 acres.” 570 U.S. at 601. In contrast, here, plaintiffs had no rights in the oysters until they executed their lease contracts, in which they agreed to be bound by Louisiana law. See supra Section VI; Tr. at 135:21-136:7 (“THE COURT: . . . [D]o plaintiffs have a preexisting right [in the oysters]? . . . [It seems] they don’t have any property rights in oysters [before signing the lease contracts]. . . . [PLAINTIFFS:] That’s right.”); Tr. at 32:24-33:2 (“THE COURT: Just to confirm, plaintiffs’ oyster leases do obligate them to comply with Louisiana law in their oyster farming? [PLAINTIFFS:] Yes, sir.”). Plaintiffs were not subject to “conditions which require[d] relinquishment of constitutional rights,” rather they agreed via lease contract to acquire property rights in oysters subject to certain restrictions. Frost, 271 U.S. at 594; Tr. at 26:19-21, 32:24-33:2. One such restriction, imposed by most—if not all—of the leases directly and by all indirectly through the obligation plaintiffs “comply with Louisiana law in their oyster farming,” is plaintiffs [*66] may not “maintain any action against . . . [the government] for any claim arising from . . . integrated coastal protection.'” La. Rev. Stat. § 56:423(B)(1) (2024); see supra Section VI. Louisiana did not, and could not, impose a condition resulting in the taking of this right because plaintiffs “never had the right to sue.” Def.’s Suppl. Br. at 18; Koontz, 570 U.S. at 606; see La. Rev. Stat. § 49:214.2(11) (2024); Id. § 56:423(A)(1), (B)(1)(a).

Whether Tyler v. Hennepin County and Related Supreme Court Precedent Are Applicable

Plaintiffs next cite Tyler v. Hennepin County and related Supreme Court precedent in support of their argument, “[s]tates do not have the unfettered authority to ‘shape and define property rights.'” Pls.’ Suppl. Br. at 9-10 (first quoting Murr, 137 S. Ct. at 1951; then citing Tyler v. Hennepin Cnty., 598 U.S. 631, 143 S. Ct. 1369, 215 L. Ed. 2d 564 (2023); then citing Webb’s Fabulous Pharmacies, 449 U.S. 155; and then citing Phillips v. Wash. Legal Found., 524 U.S. 156, 118 S. Ct. 1925, 141 L. Ed. 2d 174 (1998)). Specifically, plaintiffs contend, “[t]hough fundamental principles of [s]tate property law may define property rights, the Takings Clause limits a state’s authority to . . . circumvent federal constitutional provisions.” Id. (citing Moore v. Harper, 600 U.S. 1, 143 S. Ct. 2065, 2069, 216 L. Ed. 2d 729 (2023)). In Tyler, the plaintiff’s home was seized by the state after “the [c]ounty obtain[ed] a judgment against the property” due to outstanding property [*67] tax liabilities. Tyler, 143 S. Ct. at 1373. The state then sold the home for $40,000 and retained the total proceeds, even though the tax liability was merely $15,000. Id. at 1374. In Tyler, the Supreme Court took issue with Minnesota creating “an exception [in defining property interests] only for itself” by retaining the surplus from the sale of the plaintiff’s home when, in “collecting all other taxes, Minnesota protects the taxpayer’s right to surplus.” Tyler, 143 S. Ct. at 1379. Plaintiffs allege this is similar to the instant case, in which plaintiffs argue Louisiana made “an exception only for itself” because Louisiana has always afforded oyster lessees the right “to maintain an action for damages against any . . . entity causing wrongful . . . damage” to their beds and oysters “EXCEPT the state or federal government in relation to integrated coastal protection.” Id. at 11 (quoting La. Rev. Stat. § 56:423(B)(1)(a)).

The government disputes plaintiffs’ characterization of Tyler and related cases and argues the key distinction is, “[in those cases], state laws deemed [private property] . . . to be state property,” prompting the Supreme Court to hold, “notwithstanding the state laws’ recharacterization of formerly private property as public property, the claimants had property rights sufficient to bring takings claims.” Def.’s Suppl. Br. at 13 (first citing Tyler, 143 S. Ct. 1373-74; then citing Phillips, 524 U.S. at 156-67, 172 (invalidating a state law deeming interest earned on monies held in attorney trust accounts as part of a state program to be state property ); and then citing Webb’s Fabulous Pharmacies, 449 U.S. at 162-65 (invalidating a state law deeming interest earned on a fee held by a court to be state property)). The government states Louisiana’s oyster regime is unlike the laws invalidated in plaintiffs’ proffered cases because “[section] 56:423 does not purport to transfer any rights held under the oyster leases to the state,” meaning “Louisiana did not appropriate any interest in the oyster leases [or oysters].” Id. at 14. Specifically, the government clarifies “the difference” is no “property interest [in the ability to sue] . . . exists” here, so the government cannot and did not “recharacterize [that non-existent right] in such a way” as to render it public property. Tr. at 120:8-12.

In Webb’s Fabulous Pharmacies, the Supreme Court held a Florida statute authorizing a county to “take as its own . . . the interest accruing on . . . [certain] fund[s] deposited in the registry of the county court” violated the Fifth Amendment Takings Clause. 449 U.S. at 155-56. In doing so, the Supreme Court stated, “a [s]tate, by ipse dixit, may [*69] not transform private property into public property without compensation, even for the limited duration of the deposit in court.” Id. at 164. The Supreme Court applied this same principal in Phillips, in which it recognized “interest earned on client funds held in [Interest on Lawyers Trust Accounts] . . . is the property of the client,” including for purposes of state statutes requiring such interest be paid to “foundations that finance legal services for low-income individuals.” 524 U.S. at 160, 167 (“‘[A] [s]tate, by ipse dixit, may not transform private property into public property without compensation’ simply by legislatively abrogating the traditional rule[s] [of property].” (quoting Webb’s Fabulous Pharmacies, 449 U.S. at 164)). The Supreme Court likewise applied this rule in Tyler, stating “[t]he Takings Clause ‘was designed to bar [g]overnment from forcing some people alone to bear public burdens which . . . should be borne by the public as a whole.'” 143 S. Ct. at 1380 (quoting Armstrong v. United States, 364 U.S. 40, 49, 80 S. Ct. 1563, 4 L. Ed. 2d 1554 (1960)). The Court therefore found the plaintiff “plausibly alleged a taking under the Fifth Amendment” because Minnesota took “her $40,000 house to . . . fulfill a $15,000 tax debt.” Id. at 1380-81. In other words, the state, “by ipse dixit . . . transform[ed the plaintiff’s] private property [($25,000)] into public property without [*70] compensation.” See Webb’s Fabulous Pharmacies, Inc., 449 U.S. at 164.

Louisiana’s regulatory scheme grants plaintiffs myriad rights in the oysters and oyster beds. See Campo v. United States, 157 Fed. Cl. 584, 618 (2021) (“[P]laintiffs demonstrate rights to exclude, destroy, use, possess, sue third parties for damages, recover for larceny, alienate, and enjoy the fruits of selling oysters.”). It does not, however, afford plaintiffs the right to “maintain an[] action against . . . [the government] for [a] claim arising from . . . integrated coastal protection.” La. Rev. Stat. § 56:423(B)(1)(a) (2024). Plaintiffs, whose rights in the oysters stem exclusively from their lease contracts, which obligate plaintiffs to follow Louisiana law, therefore never had the right to sue the government for a taking arising out of integrated coastal protection, meaning this right could not be “transform[ed] . . . into public property.” Webb’s Fabulous Pharmacies, Inc., 449 U.S. at 164; supra Section VI; see also Tr. at 26:18-20, 32:24-33:2 (“THE COURT: Just to confirm, plaintiffs’ oyster leases do obligate them to comply with Louisiana law in their oyster farming? [PLAINTIFFS:] Yes, sir.”). Further, assuming arguendo plaintiffs had such a right, plaintiffs fail to explain how this case is similar to those discussed supra. There is no indication the government appropriated plaintiffs’ [*71] right to sue in a manner similar to the improper statutes at issue in Webb’s Fabulous Pharmacies, Phillips, or Tyler. Overall, it appears to the Court Louisiana did not—and indeed could not—”transform [plaintiffs’] private property” right to sue the government for a taking arising out of integrated coastal protection “into public property” because plaintiffs never had the right to sue. Webb’s Fabulous Pharmacies, Inc., 449 U.S. at 164.

Whether Knick v. Township of Scott Applies to Louisiana’s Oyster Regime

Plaintiffs finally argue Knick prevents Louisiana from allegedly “effectuat[ing] a ban of Takings claims.” Pls.’ Suppl. Br. at 13. In Knick, the Supreme Court overruled Williamson County, in which the Supreme Court had held, “if a [s]tate provides an adequate procedure for seeking just compensation [for an alleged taking], [a] property owner cannot claim a violation of the [Takings] Clause until it has used the procedure and been denied just compensation.” Knick, 139 S. Ct. at 2169 (final alteration in original) (quoting Williamson Cnty. Reg’l Plan. Comm’n v. Hamilton Bank of Johnson City, 473 U.S. 172, 195, 105 S. Ct. 3108, 87 L. Ed. 2d 126 (1985)). The Knick court recognized “property owners may bring Fifth Amendment claims against the . . . [g]overnment as soon as their property has been taken” because “if there is a taking, ‘the claim is founded upon the Constitution’ and within the jurisdiction of the Court of [Federal] Claims to hear and determine.” Id. at 2170 (first citing Tucker Act, 28 U.S.C. § 1491(a)(1); and then quoting United States v. Causby, 328 U.S. 256, 267, 66 S. Ct. 1062, 90 L. Ed. 1206, 106 Ct. Cl. 854 (1946)). The government distinguishes Knick on the grounds it dealt with “a [Supreme] Court-related exhaustion requirement in Section 1983 litigation,” not any issue relevant to this case. Def.’s Resp. Suppl. Br. at 11 (emphasis added). The government likewise alleges sections 56:423(A)(1) and (B)(1)(a) are not “blocking a right to sue the [government]” in any manner prohibited by Knick because plaintiffs “never had that right.” Tr. at 126:6-9.

In Knick, the Supreme Court, without clearly limiting its holding to suits filed under 42 U.S.C. § 1983, stated, “[t]he Fifth Amendment right to full compensation arises at the time of the taking.” 139 S. Ct. at 2170. In the instant case, Louisiana’s regulatory scheme grants plaintiffs myriad rights in the oysters and oyster beds. See Campo, 157 Fed. Cl. at 618 (“[P]laintiffs demonstrate rights to exclude, destroy, use, possess, sue third parties for damages, recover for larceny, alienate, and enjoy the fruits of selling oysters.”). It does not, however, afford plaintiffs the right to “maintain an[] action against . . . [the government] for [a] claim arising from . . . integrated coastal protection.'” La. Rev. Stat. § 56:423(B)(1)(a) (2024). Plaintiffs assented to this restriction when voluntarily signing their oyster leases. See Tr. at 26:18-20, 32:24-33:2 (“THE COURT: Just to confirm, plaintiffs’ oyster leases do obligate them to comply with Louisiana law in their oyster farming? [PLAINTIFFS:] Yes, sir.”). Louisiana therefore is not blocking plaintiffs from exercising a preexisting right to sue, rather plaintiffs never had the right to sue by virtue of “voluntarily entering into the . . . regulated” oyster industry via their restrictive lease contracts. Acceptance Ins., 583 F.3d at 857-59; see Am. Pelagic Fishing Co., 379 F.3d at 1376.

After disposing of the constitutional arguments, the court concluded that “plaintiffs, when executing their oyster lease contracts, voluntarily agreed to obtain rights in the oysters subject to the restrictions imposed by their contracts and Louisiana law” and therefore “Louisiana law unambiguously blocks plaintiffs’ claims.” Although the court doesn’t mention the cost, it certainly seems to be another instance of you get what you pay for as far as the terms and conditions of leases that in this instance, may have cost a whopping $3 per acre.

Ross Greene is a firm shareholder and chair of the firm’s Eminent Domain / Right of Way Practice Group. He focuses his practice in the areas of eminent domain, real estate, wills, trusts, estates, and business matters.

Leave A Comment