Is a claim to just compensation from eminent domain real property or personal property? Does a claim to just compensation transfer with the land or not? The answer may differ depending on various factors, including, among others, the jurisdiction in which the property is located, whether the claim stems from a formal eminent domain proceeding or inverse condemnation, and how far the condemnation process has proceeded.

Is a claim to just compensation from eminent domain real property or personal property? Does a claim to just compensation transfer with the land or not? The answer may differ depending on various factors, including, among others, the jurisdiction in which the property is located, whether the claim stems from a formal eminent domain proceeding or inverse condemnation, and how far the condemnation process has proceeded.

WHAT IF THE CLAIM IS IN A FORMAL CONDEMNATION CASE?

One would think this would be a point which would be relatively commonplace, but at least in Virginia one has to dig back in time a bit to find the case on the subject, which is Virginia-Carolina Ry. Co. v. Booker, 99 Va. 633 (Va. 1901) which states in pertinent part:

In discussing this question, Lewis, in his work on Eminent Domain, section 318, says: “The right to compensation is a personal claim, and after it has once accrued does not pass by a deed of the land. When land is occupied wrongfully or by mere consent of the owner, express or implied, no right or title to the land so occupied passes, and a subsequent deed by the owner vests the entire estate in the grantee, and such grantee, in the absence of any reservation, is entitled to just compensation for the land so occupied. The grantor in such case who has not consented to the occupation of his land may recover damages for all damages sustained up to the time of the deed, to be estimated as in an action of trespass.”

…

We have no case in Virginia adjudicating this precise question, but it clearly appears to be the policy of our statutes on the subject, that until the person or corporation entitled to acquire property for public use has so far progressed in condemnation proceedings, and against the will of the owner, as to take immediate possession thereof, no right to compensation for the land proposed to be taken and for damages to the residue of the tract accrues to the owner, and his conveyance of the locus in quo, in the absence of any reservation, carries with it to the grantee the right of compensation for the land taken, etc., when there has been a confirmation of the report of commissioners and payment to him or into court. As has been stated, there was no reservation in the conveyance of the locus in quo from W. O. Booker to The Litchfield Land Company of the right to compensation for the land proposed to be taken for the right of way of the Abingdon Coal and Iron Railroad Company, and at no time did The Litchfield Land Company treat this claim to compensation for the railroad’s right of way as an asset, but submitted to a partition of its land among its stockholders without any reference to it whatever.

99 Va. at 637-638. From this we can see that in Virginia, the right to just compensation is a personal claim that does not pass with the land, but the question then becomes has the claim accrued. Booker involves a slow-take procedure where possession did not pass until compensation was determined and paid. Therefore, the claim had not yet accrued. Given that the deed conveying the property did not otherwise reserve the claim, whatever inchoate claim there was to compensation passed via the deed.

WHAT ABOUT IN AN INVERSE CONDEMNATION CASE?

What if we are not looking at a formal eminent domain proceeding but at an inverse condemnation? The answer may well be completely different. For example, in North Carolina, condemnation proceedings are actions in rem. Redevelopment Com. of Greensboro v. Hagins, 258 N.C. 220, 225, 128 S.E.2d 391, 395 (1962). Therefore, inverse condemnation actions are considered in rem or quasi in rem proceedings because such actions depend on the complainant’s interest in the land. See id. “To prevail on their inverse condemnation claim, plaintiffs must show that their ‘land or compensable interest therein has been taken.’” Beroth Oil Co. v. N.C. DOT, 367 N.C. 333, 340, 757 S.E.2d 466, 472 (2014) (citing N.C.G.S. § 136-111). For inverse condemnation claims against the Department of Transportation, remedies are available only to those persons whose “land or compensable interest therein” has been taken. See N.C. Gen. Stat. § 136-111; National Advertising Co. v. North Carolina DOT, 124 N.C. App. 620, 623, 478 S.E.2d 248, 249 (1996) (holding that inverse condemnation claim failed because of lack of an interest in the property taken). The North Carolina Supreme Court has held that the right to bring a claim for just compensation in an inverse condemnation case passes with title to the land. See Caveness v. Raleigh, C. & S. R. Co., 172 N.C. 305, 305, 90 S.E. 244, 247 (1916). When such a transfer occurs, the previous owner of the property lacks standing to pursue such an action. Id.

FOR BONUS POINTS, WHAT HAPENS WHEN DEATH OF THE POTENTIAL CLAIMANT AND JOINT OWNERSHIP ARE THROWN INTO THE MIX?

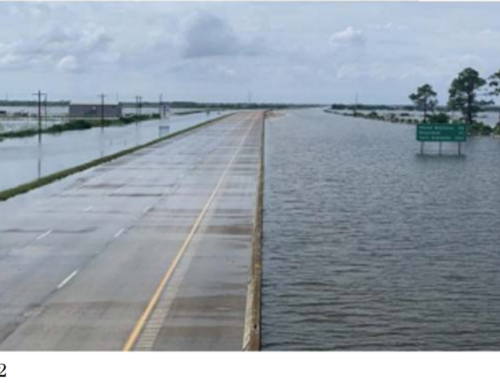

Let’s say for purposes of analysis, that there is a hypothetical formal condemnation case in Virginia in which the condemning authority filed a certificate of take on an undeveloped parcel and construction on the project begins immediately. Landowner husband and wife owned the property as tenants by the entireties. Shortly after the date of take husband dies. Wife then conveys to the parcel to her eldest son, and the deed makes no mention of the certificate of take. Wife dies. Husband and wife are survived by three children, all of the marriage. No qualification of a fiduciary for the husband. Executor qualifies for the estate of the wife. Will of the wife directs that all personalty be collected by the executor and distributed to the children in such shares as the executor sees fit. Will of the wife directs her remaining realty be given to a charity. The eldest son and the charity contact the condemning authority to say that each of them should be paid the just compensation funds deposited with the certificate of take.

We can see that we just concluded that the claim to just compensation in this situation is a personal right which does not pass with the land. Or did we? Booker dealt with a slow-take procedure. This hypothetical deals with a quick take. There is at least a potential open question here about how exactly this works as some Virginia condemnation statutes take into account whether or not the condemnor has taken possession, similar to the analysis in Booker, even though a certificate has already been recorded. At this point, just for this example, we will assume that the right to just compensation accrues in a quick take proceeding for purposes of this analysis at the time that the certificate of take is recorded whether or not the condemnor has taken possession.

Who has the claim to just compensation in this hypothetical? An answer seems to be hinted at in various points in the code. For example, when we are looking at estates in land in Virginia, the current aspects of the common law estates in land are often codified, so for a tenancy by the entirety we would be looking at Va. Code 55.1-136, which provides in pertinent part that “A. Spouses may own real or personal property as tenants by the entirety for as long as they are married. Personal property may be owned as tenants by the entirety whether or not the personal property represents the proceeds of the sale of real property.” Va. Code 55.1-136(A) (emphasis added). Potentially very helpful since it is possible to think of a claim for just compensation claim as being a claim for the proceeds of an involuntary sale of real property to the condemnor. Furthermore, since this code section is codifying a common law estate in property, the caveat about “whether or not the personal property represents the proceeds of the sale of real property” seems to imply there is case law somewhere on that point.

Since we’re looking at a claim to just compensation that arises as a result of recordation of a certificate of take, and eminent domain is a statutory procedure, we need to check the eminent domain statutes as well. Here Va. Code 25.1-308 tells us what happens when a certificate is recorded, i.e. that “A. Upon recordation of a certificate: … 3. The owner shall have such interest or estate in the funds deposited with the court or represented by the certificate of deposit as the owner had in the property taken or damaged …” Va. Code 25.1-308(A)(3). The language seems to indicate that any claim to the funds on deposit with the certificate is also held by the husband and wife as tenants by the entireties, since that was the estate in which they held the land that was taken. The statute is not perfectly on point since it does not specifically reference the claim to just compensation, but the claim to just compensation seems to me to arguably be implied by the language about “represented by the certificate of deposit” since in a certificate of deposit no funds are actually on deposit until the matter is resolved, and the right to the funds on deposit is a part of the claim to just compensation.

So then we look for the case law that Va. Code 55.1-136 seems to imply exists, and we find Pitts v. United States, 242 Va. 254, 408 S.E.2d 901 (1991), which almost answers the exact question for us:

We are aware that, in several jurisdictions which recognize that personalty can be owned as a tenancy by the entirety, the rule that we applied to the proceeds of voluntary sales of realty owned by the entireties in Oliver has been extended to the proceeds of other kinds of disposal or conversion of real estate. For example, some courts have applied the rule to the proceeds of judicial sales, condemnations, and mortgages; to the surplus remaining after foreclosure; to payments of insurance claims and damage judgments resulting from injury to realty; and to the derivatives of proceeds of voluntary sales.

Id. at 262, 408 S.E.2d at 905. Pitts cites to Real Property Proceeds – Held by Entirety, 22 A.L.R. 4th 459 (1983), which cites various other Virginia cases that deal with the disposition of proceeds from tenancy by the entirety property in different contexts.

Absent a further case exactly on point, where we likely seem to be is that the claim to just compensation is personal property, but that personal property can also be held as tenants by the entireties. Since this claim for just compensation stems from property held as tenants by the entireties, and by statute the landowner has the same interest in the funds on deposit that they had in the land, then the personal property, i.e. the claim to just compensation, is held as tenancy by the entireties property as well, so that when the husband died, his share of the claim to just compensation also passed to automatically to his wife as the surviving joint tenant at death, outside of probate. Wife has also died, so who among the persons involved with her estate is entitled to the funds? The answer for this hypothetical would seem to be the executor of the estate of the wife and neither of the persons asking for the funds.

CONCLUSION: JUST BECAUSE SOMEONE SAYS THEY ARE ENTITLED TO JUST COMPENSATION DOES NOT MEAN THEY ARE THE CORRECT PERSON.

This blog post obviously does not comprise a complete matrix of all of the different permutations one can have as far as jurisdiction, type of claim, timing, and other facts, that can make determining who possesses the claim to just compensation a complicated question, and there are still more potential complications. (It can get even more complicated if title defects are thrown into the mix). The primary takeaway here is that the question should be asked and analyzed to avoid paying just compensation to the incorrect persons or parties, and that experienced condemnation counsel should provide this answer to the condemning authority because of the numerous jurisdiction and fact specific nuances involved.

Ross Greene is a firm shareholder and chair of the firm’s Eminent Domain / Right of Way Practice Group. He focuses his practice in the areas of eminent domain, real estate, wills, trusts, estates, and business matters.

Leave A Comment