If you claim to have an implied easement, do you have to prove the actual location of the easement on the ground? Yes, you do, as the Virginia Court of Appeals recently found in Morris v. Parker, 2024 Va. App. LEXIS 28, affirming the defense win in the trial court. Credit for the win at both levels goes to the brilliant duo of Mark Baumgartner and Kristen Jurjevich with our firm, representing the appellees / defendants. I only consulted on the case infinitesimally prior to trial. Regardless, on to the facts of the case as set forth by the Court of Appeals:

If you claim to have an implied easement, do you have to prove the actual location of the easement on the ground? Yes, you do, as the Virginia Court of Appeals recently found in Morris v. Parker, 2024 Va. App. LEXIS 28, affirming the defense win in the trial court. Credit for the win at both levels goes to the brilliant duo of Mark Baumgartner and Kristen Jurjevich with our firm, representing the appellees / defendants. I only consulted on the case infinitesimally prior to trial. Regardless, on to the facts of the case as set forth by the Court of Appeals:

In October 1998, the Morrises acquired a tract of land in Chesapeake consisting of two parcels, “Parcel 3” and “Parcel 5” (collectively, the “Morris property”). At the time of conveyance, Parcel 5 comprised the east side of the Morris property. The 1998 deed incorporated a land survey showing the two parcels. As reflected in the survey, a right of way named “Flurry Road” (also referred to as “Fluridy Road”) borders Parcel 5 on its east side. The Morrises have never used any right of way they claim to be Flurry Road; instead, they access the Morris property via Sanderson Road (southern border) and Foreman Road (western border).

The Parkers own land on the other side of Flurry Road as shown in the survey, which they acquired in 2003 (collectively, the “Parker property”). The Parkers’ property includes a gravel road entirely inside of their property (the “gravel road”).

In 2017, the Morrises re-subdivided the Morris property, eliminating Parcel 5 and creating a smaller “Parcel 5-A” that now borders Flurry Road as depicted on a 2017 plat. The Morrises wanted to sell Parcel 5-A and install a driveway connecting Parcel 5-A to the gravel road on the Parker’s property. Despite the gravel road being inside the Parker property rather than between the Parker property and the Morris property, the Morrises asserted the gravel road was Flurry Road and that it would provide access for their new Parcel 5-A to a public thoroughfare to the south. When the owners of the gravel road, the Parkers, did not agree, the Morrises filed a declaratory judgment action against the Parkers seeking an order “confirming [the Morrises’] right . . . to use [the gravel road] to access the Morris Property” and to “enjoin the [Parkers] from interfering with or otherwise impeding that right.”

At trial, the Morrises introduced evidence, including expert testimony from a title examiner, showing that the Morris property and the Parker property were once owned by a common grantor, that the Morrises’ deed as well as the Parkers’ deed, together with other deeds and documents in their chains of title, consistently describe their respective properties by reference to a 1909 subdivision plat recorded in the clerk’s office for the city of Chesapeake, and that this 1909 subdivision plat depicts the Morris property and the Parker property abutting Flurry Road, directly across from one another.

The title examiner testified that, consistent with the 1909 subdivision plat, the plat attached to the Parkers’ 2003 deed shows that the Parker property abuts the east side of Flurry Road and that Flurry Road, as platted, is not located within the boundaries of the Parker property. She stated that, in her expert opinion, the land records established that neither the Morrises nor the Parkers owned the platted Flurry Road.

The title examiner did not testify about the physical location of Flurry Road, merely its location as platted in the land records. Regarding the platted Flurry Road, the title examiner testified that she did not know “[w]hether it was developed or not, whether it’s gravel or dirt or whatever” and “[t]here’s no way to really tell exactly where it is.” The Parkers disputed that the gravel road was the same as the Flurry Road depicted in land records. No one presented any testimony from a surveyor linking up the drawn location of Flurry Road to any road on the ground.

After considering the evidence and post-trial briefs, the court issued a letter opinion finding that the Morrises failed to “establish an implied easement.” To reach this conclusion, the court applied a three-prong test for an implied easement from prior use from Russakoff v. Scruggs, 241 Va. 135, 400 S.E.2d 529, 7 Va. Law Rep. 1381 (1991):

While the extent of the easement rights is determined by the circumstances surrounding the conveyance which divides the single ownership, the existence of the [implied] easement is established on a showing that (1) the dominant and servient tracts originated from a common grantor, (2) the use was in existence at the time of the severance, and that (3) the use is apparent, continuous, and reasonably necessary for the enjoyment of the dominant tract.

Id. at 139 (alteration by trial court).

The court “[a]ssum[ed] without deciding that the first element, the presence of a common grantor, ha[d] been established.” However, it found “no evidence . . . that the use was in existence at the time of the severance or that it was apparent, continuous, and reasonably necessary.”

The trial court entered a final order incorporating its letter opinion and dismissing the matter with prejudice. The Morrises appealed.

The Morrises argued on appeal that the trial court misapplied the law of implied easements, but the Court of Appeals did not reach the point, instead affirming the trial court on a “right for the wrong reason” basis. Instead of getting into the even more obscure points about an implied easement from prior use, the Court of Appeals held that the Morrises failed to prove a key threshold fact: the physical location of their claimed easement.

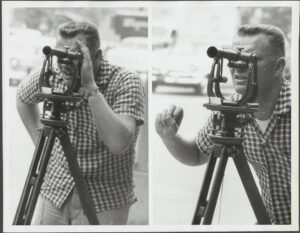

The Morrises did not present testimony from a surveyor establishing that the gravel road actually present on the Parkers’ property corresponds to Flurry Road shown in the land records. The Court of Appeals did note that “failure to present testimony from a surveyor is not per se fatal to an implied easement claim,” so there would seem to be fact patterns where you do not have to have a survey done, but the implication from the opinion seems to be that in cases attempting to establish an easement, that it may be a very good idea to have a survey done and have the surveyor available to testify at trial.

Ross Greene is a firm shareholder and chair of the firm’s Eminent Domain / Right of Way Practice Group. He focuses his practice in the areas of eminent domain, real estate, wills, trusts, estates, and business matters.

Leave A Comment