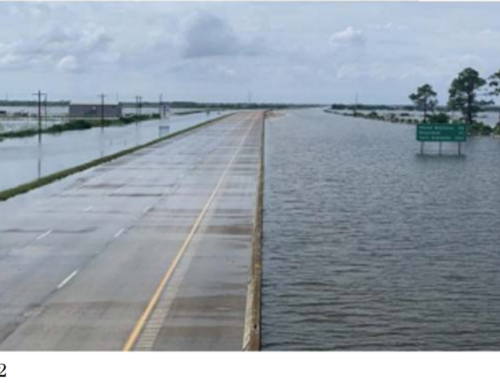

Wetlands are a particularly important and fragile ecological resource. In recognition of that, the federal government has long interpreted the Clean Water Act broadly to protect not only wetlands that are directly connected to traditional waterways but also those more remote wetlands that have some connection to such waterways. In Sackett v. EPA, the Supreme Court ended federal protection for more remote wetlands. The consequences of the decision for proponents of infrastructure projects will vary by state. In Virginia, save for one class of project, the consequences, on paper at least, should be minimal.

Broadly speaking, the Clean Water Act prohibits the discharge of a pollutant to the navigable waters. The term “navigable waters” is defined in the statute to mean “the waters of the United States, including the territorial seas.” As this is not exactly the most illuminating definition, the two agencies charged with enforcing the Clean Water Act, the Environmental Protection Agency and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, have stepped in at various points to define what “waters of the United States” means. Though the definition changed over time, it was always fairly expansive. As relevant here, the term included all waters that could affect interstate or foreign commerce. The definition explicitly included wetlands “adjoining” other waters. The term “adjoining” was given a broad definition so that any wetland that had a nexus to a traditional “water” was regarded as being within the coverage of the Clean Water Act. The agencies explicitly recognized that all wetlands within the United States, no matter how remote from traditional waters, could arguably be covered under this definition.

Enter the Sacketts. They are a couple in Idaho who purchased a plot of land that included wetlands in 2004. The Sacketts began filling the wetlands on their land so that they could build a house on it. The EPA informed the Sacketts that their lot included protected wetlands and ordered them to undertake a restoration plan or else face fines of up to $40,000 per day. Under the EPA’s view, the wetlands on the Sackett property were “adjacent” to a nearby lake because the wetlands were on the other side of a road from an “unnamed tributary” (elsewhere in the opinion characterized as a ditch) that flowed into a non-navigable creek that itself flowed into the lake. The Sacketts sued the EPA under the Administrative Process Act, arguing that the EPA lacked jurisdiction because their property did not include “waters of the United States.”

At the Supreme Court, every justice agreed that EPA’s interpretation went too far and that the wetlands on the Sacketts’ property were not “waters of the United States.” The majority held that “waters of the United States” referred to a relatively permanent body of water connected to traditional interstate navigable waters. This would likely include lakes, rivers, and creeks that are tributaries of navigable waters. Only those wetlands that are “adjacent” to such waters are subject to regulation under the CWA. The majority held that “adjacent” means that the wetlands have a continuous surface connection with the water so that it is difficult to distinguish between the water and the wetland. Justice Thomas wrote separately to emphasize that “waters of the United States” must be interstate waters, so that wholly intrastate waters would be excluded from regulation under the Clean Water Act under his reading. Other justices wrote separate concurring opinions to argue that wetlands separated from a traditional water by a natural or man-made barrier should still be considered to be “adjacent.”

The result of this holding is that fewer wetlands are subject to federal regulation. State regulation of wetlands were left untouched. Protections afforded more remote wetlands will therefore vary state by state.

In Virginia, all wetlands are subject to regulation by the Department of Environmental Quality, and tidal wetlands are regulated by localities or, if the locality has not adopted a model ordinance, the Virginia Marine Resources Commission. In the wake of the Sackett ruling, DEQ has promulgated a guidance document that assures the public that its authority to regulate wetlands under state law is expansive and continues uninterrupted. The guidance, a copy of which can be found here, notes that Virginia will continue to require delineations of wetlands and surface waters along with applications for its permits, which are still generally required to the same extent as they were before Sackett. It also provides some indication of the strategy it will use to handle the anticipated increased workload. Thus, for most infrastructure projects that will cross wetlands, the same joint permit application with the same wetlands delineations will be required and should be submitted to the appropriate state agencies for processing.

The one exception to this will be interstate natural gas pipelines. The Natural Gas Act preempts state-level environmental regulation of interstate natural gas pipelines, though it preserves state authority to regulate such pipelines pursuant to § 401 of the Clean Water Act. Under that authority, Virginia DEQ had the authority to review all pipeline crossings of wetlands in the state. Now, with the more limited scope of the Clean Water Act, it is doubtful that DEQ could review crossings of remote wetlands.

As the agencies with responsibility for regulating wetlands at the state and federal level continue to digest Sackett, more guidance on this topic will surely follow.

Matt Hull is a Pender & Coward attorney focusing his practice on eminent domain/right of way, local government, and waterfront law matters.

Leave A Comment