III. Preparation

Typos and errors. Your report and/or disclosure are going to be one of opposing counsel’s main lines of attack. They need to be well-researched, well-supported, and as close to 100% error free as possible. Comb them with a ruler if you have to. No one wants to see typographical errors up on the display in court in a report that you have just testified you were paid several thousand dollars for, in a case where large sums of money are on the line. It seems petty, but there is no denying that typographical errors can have a negative effect on your credibility to the jury. If you do miss one and it comes up when you are being questioned, correct it gracefully without being visibly flustered. If you are in a deposition, your attorney may want you to hand correct and initial the copy of your report attached to the deposition.

Supporting or predicate witnesses. If you have to have or could use the opinions of other expert witnesses in formulating your opinions, make sure to discuss that with the attorney for your side at your earliest opportunity. Do not assume that the attorney knows what you need on that front and that it is just going to appear when you need it. The attorney could equally assume that you are retaining your own subordinate experts. Figure out who is locating and retaining them on the front end. It takes time to find and retain additional experts, and time to get approvals for them and get them engaged.

Themes. Litigators generally are planning to use one or more themes to tie their case together. When you are discussing the case with the attorneys for your side, see if they are comfortable telling you what the theme or themes they are working on are. If you know what themes they are using to try to case together, it can help you contribute to the case. Really, they should tell you what the theme is, but if they do not, ask. This helps you understand why they are asking the questions they are asking.

Ask for the documents and information you need, proactively. Often we do not have the information that you would prefer to review. We need lead time to take your list of what you need in the case, and issue discovery in order to obtain that information. I highly recommend preparing a list of all of the information and documents that you need to prepare your report or could possibly want to have in the case, and then telling that list to your counsel as soon in the case as you can, so they have an opportunity to obtain those documents in discovery and get them to you. Discovery is not a quick process, so do not expect to be able to wait until the last minute and ask counsel to have these documents.

If you are aware of other potential sources of data about the property, let your counsel know. While your attorney will have to fight with the opposing attorney to get anything in the discovery process from the landowner, it often can be much easier to subpoena records from third parties. If you know of any third parties who have interacted with the property, let your attorney know who they are and what you know about them. For example, if you know the property is listed by an agent or broker, let your attorney know, as he can likely subpoena that person’s file on the property.

Bring areas of concern to the attention of counsel as soon as you can. Figure out in advance the issues that concern you, or any questions that you feel nervous or afraid of being asked, and ask your counsel in advance how they would like to deal with them. If there are any potential soft spots/problem areas in your assigned area of the case that you have identified, explain them your attorney verbally, and see how he would like to proceed.

CV/Resume. Whether you produce a written report or not, in a litigation there will come the point where your counsel has to disclose or designate your opinion. Counsel will need a current copy of your CV or resume, so make sure you have that completely up to date including all relevant experience you have pertinent to the case you’re in. If you have multiple areas of expertise and some are not relevant to the case you are in, you might want to tailor your CV or resume to highlight the expertise you have that is relevant to the current case. Your CV/Resume will be another main line of questioning / attack from opposing counsel. Know what is on there. Know what is not on there. Whatever is on there, be well prepared to discuss it as you will be questioned about it.

Preparing for Direct Examination. Direct examination is one of the hardest parts of a trial. Often experts are not prepared for it as they should be, because they and everyone else are so concerned about cross-examination, and because as I noted above, deposition provides you some amount of practice at being cross-examined by opposing counsel. You and the attorney need to have worked together, in advance, extensively to prepare your direct examination. You need to know what questions they are going to ask, and what your answers should be generally, but not have them so memorized that you sound like a robot reading a script. Don’t read from a script or memorize a script if you can avoid it. It robs your voice of authority and authenticity.

Your attorney cannot ask you leading questions. They have to ask open ended questions on direct, so as noted above, it is helpful if you know the themes of the case and the gist of what counsel is trying to elicit so you don’t freeze up if your attorney has to go off of the prepared list due to some development at trial.

Do not stray beyond the limits of your expertise.

Sit forward and turn and talk to the jurors. While on direct your counsel is asking you questions, you are not really answering him. This is just a vehicle for you to be able to talk to the jurors so make sure you are looking at and talking to the jurors.

Do not talk down to the jury or judge. Nobody likes being talked down to.

Keep it simple and understandable. Industry jargon and acronyms are meaningless to jurors. Remember that you have a very diverse jury pool. The people on the jury may not have your frame of reference, so again, keep it very simple and understandable and do not assume “everyone knows _____.” If you have to use terms that are not absolutely commonly understood, define them. Better to define a term than risk having the jurors not understand its definition in this context.

The pattern of direct questions should allow you to summarize what you are going to tell the jury, let you tell it to them, and then tell them what you told them. Don’t assume they’ll get it on the first go.

If you and your counsel have identified problems with your analysis or report, discuss “pulling the sting” on those issues prior to taking the stand. This is just acknowledge these issues on direct yourself, rather than leaving them for opposing counsel to pull out and beat you up on cross.

Avoid long narrative answers (Jurors and Judges have a limited attention span)

Use visual aids if possible. Help your counsel put them together if you can. Make sure your counsel has practiced with you with the visual aids they intend to use. All kinds can be good if put together well, i.e. diagrams, photos, videos, etc. One of the best things that you can do to make yourself excel as an expert witness and make your attorneys love you, is be able to make visual aids that are actually understandable and persuasive to jurors. Again, these need to be simple and understandable. Too often, experts in right of way prepare a visual aid and it is a jumble of tiny lines and symbols and colors that you can hardly read with a magnifying glass if you’re a trained professional, much less a lay person looking at it from across the room. Simple visual aids. Primary colors. Only the absolutely necessary data points. Avoid spreadsheets, graphs, etc., if you can. If you can’t, keep them very straightforward. Usually try to only have one point you are getting across per exhibit. Those comparable sales spreadsheets you commonly see used as exhibits, they easily turn into visual salad for bored jurors trying to understand all the data points. If you have to use them, try to use multiple boards and colored sections to focus attention.

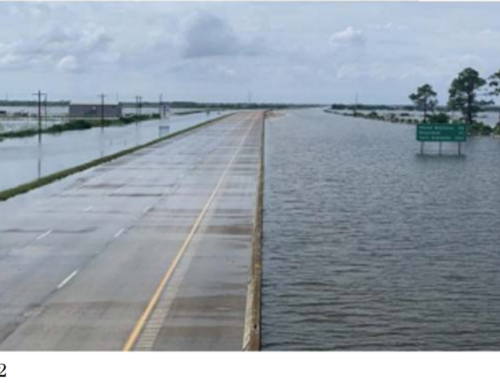

A picture is truly worth a thousand words. If you are talking about the property, try to have pictures of it to refer to about the specific issue if possible. Make sure in advance that you and counsel have sufficient photographs of the property, its various elements, and various angles, to illustrate what your testimony is about it if possible.

Preparing for Depositions and Cross-Examination.

Prepare yourself sufficiently as far as you can. You need to study and prepare for your report, your deposition, and trial, as if were studying for an important final examination. Success in depositions and cross-examination is often more perspiration (preparation) then inspiration. If the case is large enough to support it, the best preparation is for counsel to stage a mock examination of you, or several rounds of mock examination of you, so that you can become comfortable with potential questions and the tempo of questions, objections, and answers in cross-examination. If they can, they should use a different lawyer than the one you are usually working with in the case to do this work, so it feels more real to you.

Your attorney cannot talk for you in depositions or cross-examination.

You cannot ask your attorney questions in a deposition or cross-examination.

Control your body, your posture, and your voice. The best expert witnesses are not necessarily the most brilliant or even competent people in their field. If he comes off as Mr. Rogers and you come off as insecure and angry, in all likelihood the jury believes him and not you. You want to appear calm, collected, and if at all possible, kind. You do not want to appear combative, angry, or emotional. You also don’t want to show nervous habits. You want your eye contact to be appropriate, and your hands and body to be still, relaxed, and in an appropriate posture. This is an entire area of coaching and too much for today, but ask your counsel to review your body language and provide appropriate feedback about how you can improve it if necessary.

ALWAYS TELL THE TRUTH. Opposing counsel wants to embarrass you into changing your story, shading the truth, or lying, and he is ready for it. That being said, most of what you will be testifying to in eminent domain is opinion, not fact.

Never volunteer information. Answer the question that is asked. Don’t ramble.

Make sure you understand the question before answering. A lot of people start thinking about their answer before the other person finishes the question.

Take time to think about the question and your answer. Don’t rush. You do not owe opposing counsel a speedy answer, even if he acts like you are taking too long or that he has somewhere else to be. It is an act to try to rush you into a bad answer.

Remember that sometimes you cannot remember.

Be patient. Be polite but firm.

Never lose your temper. Avoid anger when someone questions your opinion, character, or bias. If it does not affect you, it is not likely to affect the jury. If you react to these lines of attack, the jury may think there is some truth to them.

Speak clearly. You want the transcript to be clean and to accurately record what you say.

Finish your answer. If opposing counsel cuts you off, finish your answer from the previous question, then proceed with answering the new question. If after finishing the answer to the previous question, you don’t remember his current question, you can ask opposing counsel to repeat the question.

Always let the attorney finish his question before you answer. Don’t cut them off. This is another variant of make sure you understand the question, and speak clearly. If you cut them off or talk over them it makes a jumbled and hard to understand transcript. It also may result in you answering a question better for them than what they might have asked if you let them finish.

Carefully review any document that you are asked about before answering. If they put something in front of you, don’t just assume it is what they tell you it is.

Listen to objections. Your attorney will be there with you and he may object to the questions. Listen to his objections as they may contain clues for how to answer, and regardless, if he is objecting, there is something to be wary of in that question.

Be careful and do not fall for the lawyer’s style. If he is being mean to you, it is an act. If he is being nice to you, it is an act. Neither one matters. Both are designed to cause a reaction from you to his benefit.

Do not bring any documents to the deposition unless your lawyer approves it in advance.

Never assume facts you know are false.

Be comfortable. You’re allowed to go to the bathroom. You’re allowed to ask to have a comfortable temperature in the room. Don’t be afraid to ask to go to the bathroom, get a drink, or have the temperature turned up or down.

Do not accept a question which attempts to summarize your prior testimony. If for some reason they absolutely insist on hearing your previous testimony, you can suggest to them that they have the court reporter read it back.

Be careful of the silent treatment. This is the opposite of the note above about being rushed. If the lawyer just sits there and isn’t asking questions, he may just be thinking, but more commonly, he is deliberately leaving dead air hoping that you won’t be able to resist chatting in order to fill the space. Again it is a tactic just to get you talking. Don’t be unpleasant, but don’t talk or chat during a deposition if you don’t have to.

Be careful of the end of the line question: Is this everything you recall? Summary questions like this are traps so that opposing counsel can feign outrage later if you try to say something that wasn’t in the deposition, and say you told him that you had discussed everything. The answer to this sort of summary question is generally some form of “That is all that I recall at this time.”

Make sure you are familiar with your prior publications and prior testimony in other matters. Opposing counsel will attempt to use them against you.

Ultimately, when you are testifying as an expert witness you are a teacher on the stand. In order to make sure the information or expertise you are trying to convey is received by the audience, make sure to be likable, human, honest, entertaining, and energetic.

If you enjoyed this article, please feel free to click the subscribe button below if you are not already a subscriber.

Ross Greene is a firm shareholder and chair of the firm’s Eminent Domain / Right of Way Practice Group. He focuses his practice in the areas of eminent domain, right of way, real estate, wills, trusts, estates, and business matters.

Leave A Comment