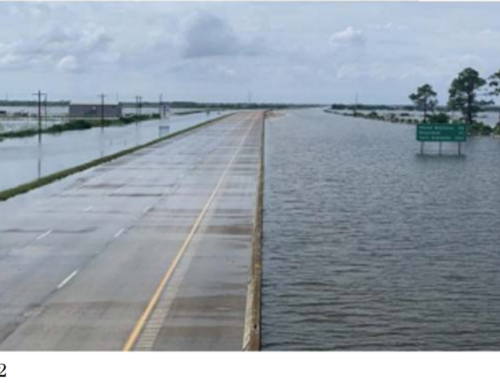

A view of the Nansemond River

The interaction of oystermen and water pollution in the Tidewater area is nothing new, and a similar claim was addressed by the Supreme Court of Virginia in 1919 in Darling v. City of Newport News. The Supreme Court of Virginia held in Darling that the holders of oyster ground leases take their leases subject to the risk of pollution of the water, particularly given the known and ongoing water quality issues in Hampton Roads and the related rivers, including the Nansemond River. The plaintiff in Darling even appealed to the United States Supreme Court, which also upheld the Supreme Court of Virginia’s ruling.

The plaintiffs in the current case appealed to the Supreme Court of Virginia arguing that Darling was obsolete given the passage of environmental protection statutes in the intervening years. The Supreme Court of Virginia rejected the plaintiffs’ claim. It noted that the first inquiry in an inverse condemnation case is whether a government action has affected a property interest that is cognizable under the law. The Supreme Court of Virginia found that the oystermen could not maintain their suit because of the extremely limited property rights they gained under their leases of government-owned submerged land for oyster planting. Leases of these sorts of publicly owned lands are strictly construed and only convey very limited rights, given that the leases involve private individuals using public resources for their private gain. The court in Darling recognized that the leases did not confer any right to pollution-free water or a commercially-viable oyster harvest. Just like the plaintiff in Darling, the oystermen did not have a property right to control the contents of the water that inundates the river bottom that they rent from the state. The $1.50 per acre per year that they pay to lease public property from the state does not get them that right. The court noted that the Virginia Code authorizes relief from rent payments if “any natural or man-made condition arises which precludes satisfactory culture of oysters in that area.”

It is important to note that the Supreme Court of Virginia did not indicate that the defendants have the right to pollute the river. Instead, the Court indicated that the plaintiffs do not own the necessary property rights to make a claim for inverse condemnation.

The case is styled Johnson, et al. v. City of Suffolk, et al., and a copy of the Supreme Court of Virginia’s opinion can be found here. Dave Arnold, myself, and Matt Hull, all of Pender & Coward’s Eminent Domain / Right of Way Practice Group and Local Government Practice Group represented the City of Suffolk in this case. If you want to hear the oral argument before the Supreme Court of Virginia, link is available here 191563 Johnson, et al. v. City of Suffolk, et al.

Ross Greene is a shareholder with Pender & Coward, P.C., and also the editor of this blog. In his right-of-way practice, Ross represents condemning authorities, including state government agencies, utilities, municipalities, and right of way consultants.

Ross Greene is a shareholder with Pender & Coward, P.C., and also the editor of this blog. In his right-of-way practice, Ross represents condemning authorities, including state government agencies, utilities, municipalities, and right of way consultants.

[…] Ever think about who owns the bottom of a river? At least in Virginia’s tidal saltwater rivers, the answer is often that the state owns it and that people can rent state-owned river bottom in order to plant oysters for $1.50 per acre per year. So what does one get for a rent of $1.50 per acre? How about the right to sue the government if the quality of the water in the river isn’t to your liking? Read on to find out the answer in a recent opinion from the Supreme Court of Virginia addressing allegations of inverse condemnation of leased oyster planting grounds. (Hint: If you guessed that for $1.50 per acre per year that is not a right the lessee receives, you are correct.) Read More. […]